Newsletter No. 10 Observatory on the SJP

Newsletter No. 10 Observatory on the SJPNewsletter # 10. The granting of amnesty and rights of victims: analysis of Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020 of the Judicial Panel for Amnesty and Pardon

Translated with the support of United Nations Online Volunteering and the volunteers Lilian Kassin, María Alejandra Saldarriaga and Alejandro Gallegos

This newsletter analyzes the granting of amnesty and its implications for the rights of victims based on Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, issued by the Judicial Panel for Amnesty and Pardon (SAI for its Spanish acronym) on February 12, 2020, by means of which the amnesty benefit was granted to Marilú Ramírez Baquero in relation to his responsibility for participating in the detonation of a car bomb at the Superior War College of Bogotá in 2006.

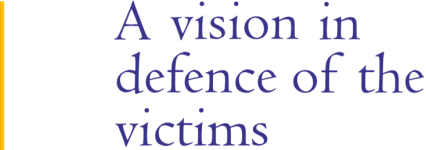

The Peace Agreement established the granting of amnesties for political and related crimes for former members of the FARC-EP. For the implementation and regulation of the granting of amnesties, Law 1820 of 2016 and Decree Law 277 of 2017 were approved, in accordance with which it is appropriate to grant amnesty when the following elements are met:

Graph 1. Areas of application of the amnesty

Own elaboration based on Law 1820 of 2016 and Legislative Act 1 of 2017)

To establish whether the material of amnesty application scope is met, it must be taken into account that art. 15 of Law 1820 establishes that rebellion1, sedition2, riot3, conspiracy4 and seduction, usurpation and illegal retention of command5 are political crimes. Likewise, subsection 1 of art. 16 of Law 1820 contains the following list of related crimes:

(…) seizure of aircraft, ships or means of collective transportation when there is no contest with kidnapping; constraint to commit a crime; violation of someone else's room; unlawful violation of communications; offer, sale or purchase of an instrument capable of intercepting private communication between people; unlawful violation of official communications or correspondence; illicit use of communication networks; violation of freedom of work; insult; slander; indirect insult and slander; damage to someone else's property; personal falsehood; material falsehood of an individual in a public document; obtaining false public document; conspiracy to commit a crime; illegal use of uniforms and insignia; threats; instigation to commit a crime; fires; disturbance in public or official public transport service; possession and manufacture of dangerous substances or objects; manufacture, carrying or possession of firearms, accessories, parts or ammunition; manufacture, carrying or possession of weapons, ammunition for restricted use, for the exclusive use of the armed forces or explosives; disturbance of democratic contest; constraint to the suffragette; suffrage fraud; fraud in registration of ID cards; corruption of the voter; fraudulent vote; contract without compliance with legal requirements; violence against public servant; leakage; and espionage.

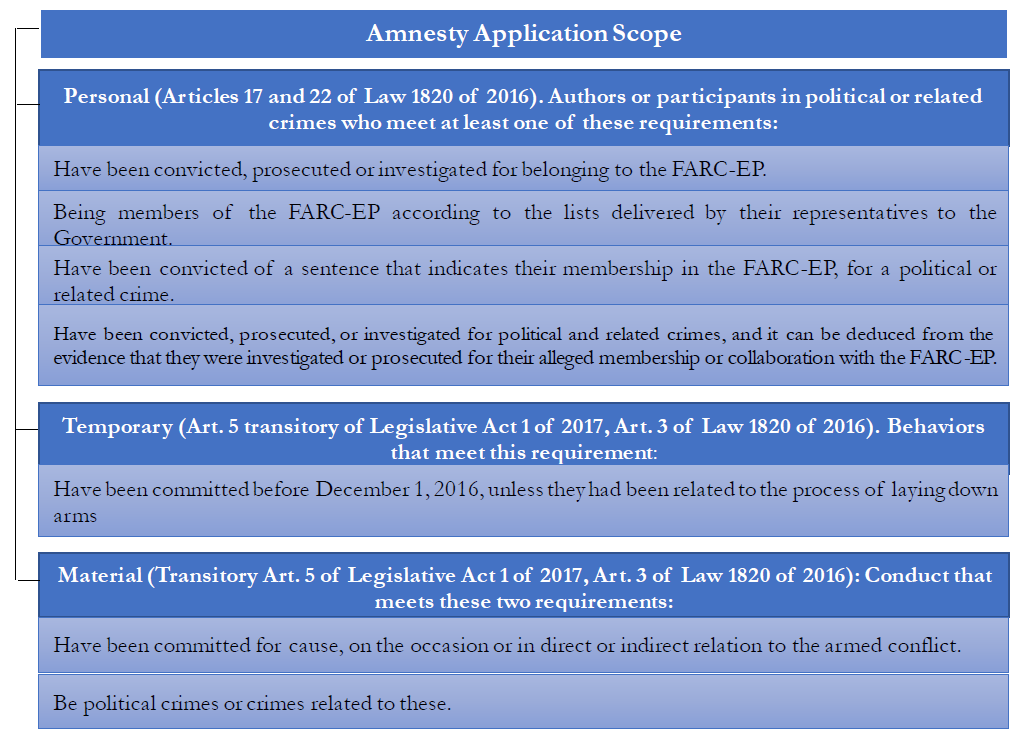

In addition to the crimes established as explicitly related in art. 16 of Law 1820, the SAI can determine whether a common crime is related to political crimes by analyzing the factors of connection established in art. 23 of Law 1820 of 2016:

Graph 2. Factors of connection with political crimes to Law 1820 of 2016

(Own elaboration from art. 23 of Law 1820 of 2016)

Amnesty can be of two types: de jure amnesty and courtroom amnesty. The de jure amnesties were automatic and applied to conducts established as political crimes in art. 15 of Law 1820 or as related crimes in art. 16 of the same, fulfilled the fields of application. The courtroom amnesties are applicable in cases where the conduct does not clearly fit into the political and related crimes specifically established in the Law, making it necessary to apply the criteria of art. 23 of Law 1820 to determine its connection, provided that the fields of application are met.

The granting of amnesty has the consequences of the immediate freedom of the beneficiary and the termination of the criminal action, the main and accessory criminal penalties, the action for compensation of damages for the amnestied crime, the responsibility derived from the repetition action (if the amnestied person was performing public functions) and the investigations or disciplinary or fiscal sanctions related to the amnestied conduct6. However, the amnesty does not exempt the duty to contribute to the clarification of the truth and the satisfaction of the rights of the victims. Therefore, the access and maintenance of the benefits of the amnesty are subject to a conditionality regime, which obliges the beneficiaries to contribute to the SJP, the Commission for the Clarification of the Truth, Coexistence and Non-Recurrence and the Unit for Search of Missing People, to guarantee the rights of the victims for the term of their validity.

Likewise, the victims of the events submitted to the amnesty process before the SAI have the right to participate in the proceedings. In accordance with art. 46 of Law 1922 of 2018, the victims must be notified of the resolution through which knowledge of the facts is advocated, so that they can give their opinion on the amnesty request and its annexes, and also of the one that closes the process, for them to give their opinion on the decision to be taken in the case. In addition, resolutions that deny or grant amnesty have the right to appeal for reconsideration before the same Judicial Panel and on appeal before the Appeals Chamber of the Peace Tribunal.

As expected, the SAI faced serious judicial congestion during the first years of its operation. On January 22, 2019, the State Council evidenced “an unconstitutional state of affairs regarding the distribution of matters for processing in the judicial secretariat of the Judicial Panel for Amnesty or Pardon of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, which has led to a growing dam in the distribution of requests to the interior (…)”7. On March 20 of the same year, the SJP's Revision Chamber declared the existence of “a recurring violation and, at the same time, a threat to the fundamental right of access to the administration of justice for the people who will go to that body in the future to that judicial organ, in view of the fact that, as a consequence of the repression of requests for freedom, their resolution will not be adopted in the terms of the law”8. However, as of February 28, 2020, the SAI had granted 203 and denied 1,133 amnesties to former members of the FARC-EP9.

In 2005, Marilú Ramírez Baquero (hereinafter, the appearing party) took the Comprehensive National Defense Course offered by the Superior School of War. While attending this course, he supplied intelligence information on the School's facilities to the Antonio Nariño urban structure of the FARC-EP in Bogotá. Based on the information provided, on October 19, 2006, the FARC-EP triggered a car bomb in a parking lot in front of the Superior School of War, near the Nueva Granada Military University, producing an explosion that caused injuries to the military and civilians and generated various material damages. The appearing party was prosecuted and sentenced by the ordinary criminal justice in 2015 for her participation in these events, under the crimes of terrorism, attempted homicide and aggravated personal injuries, declaring that the criminal action is prescribed for the crimes of rebellion and damage in aggravated foreign good. The decision was confirmed in the second instance and it was appealed in cassation before the Supreme Court of Justice for the year 2016, when Law 1820 was issued, therefore the file was sent by said corporation to the SJP.

Upon learning about the file, the SAI in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-202 decided to grant the benefit of amnesty to the appearing party for the events indicated, in accordance with the provisions of Law 1820 of 2016. To make this decision, the SAI had to verify that the areas of temporal, personal, and material application for the granting of the amnesty were met. According to the SAI, the temporary application scope was fulfilled because the detonation of the car bomb occurred on October 19, 2006, before the signing of the Peace Agreement. In turn, the personal application scope was met because the appearing party was a member of the FARC-EP, a quality that had been accredited by the Office of the High Commissioner for Peace and that was attributed to her in the ordinary criminal justice file.

When evaluating the material application scope, the SAI considered that the behavior of the appearing party was related to the internal armed conflict because it was part of the FARC-EP's war strategy against the Public Force and, given that it did not constitute a political crime or a crime explicitly established as related in Law 1820, it proceeded to determine its connection from the analysis of its inclusive and exclusive factors. Regarding the inclusive factors of connection, the SAI pointed out that the detonation of the car bomb was "an action typical of the rebel action of the FARC-EP guerrilla, within the armed conflict in which it clashed with the Colombian State (…)”10, whose taxable person was the State and its constitutional regime.

When analyzing whether the excluding factors of connection were present, the Judicial Panel developed a more detailed analysis and proceeded to resolve the most complex legal problem in the case. For the SAI, the facts were related to the rebellion and they had the intention of developing the rebel action, but it had to be determined if they constituted a war crime11, since in that case the amnesty would not be appropriate. To do this, it proceeded to analyze whether the detonation of the car bomb at the facilities of the Higher War College had constituted a violation of international humanitarian law (IHL).

In this sense, the SAI determined that the detonation of the car bomb in the facilities of the Superior School of War was a valid act within the framework of IHL and not a war crime, based on the following considerations:

|

In its analysis of the specific case, the SAI determined that the detonation of the car bomb at the Superior School of War was directed against a military objective, pursued a specific and direct military advantage, caused incidental damages to civilians that were proportional to said advantage and that feasible precautions were taken to minimize such damage. |

By virtue of the analysis that we have summarized, the SAI concluded that the attack was carried out in accordance with the rules of IHL and that it was not appropriate to apply the exclusionary criterion of connectedness indicated in the case, because the conduct did not constitute a war crime. With this conclusion, the Panel closed the analysis of the material scope of application, and decided that it was appropriate to grant amnesty to the appearing party, subject to the conditionality regime and, in particular, to the contribution to the full truth and the performance of public acts of recognition and apologies to the victims and affected, always observing good faith and due respect.

According to the foregoing, it is observed that in the case the SAI applied IHL. In this regard, it should be taken into account that, first, the determination of the connection with the political crime of the conduct in the case, in accordance with Law 1820 of 2016, required the SAI to determine whether the conduct analyzed was a war crime and, therefore, whether it had respected the rules of IHL. Second, the SJP is governed not only by domestic criminal law, but also by IHL, international human rights law, and international criminal law. Thus, the legal classification of the SJP must be made considering the national and international legal framework and may vary from the legal classification initially made by the ordinary criminal justice, respecting the principle of favorability. In this case, the SAI also applied the rules of IHL, by virtue of the principle of favorability and due to its specificity in dealing with the facts of the case. On previous occasions, the SAI has carried out analyzes similar to the one developed in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, verifying whether the potentially amnistiable conduct respected the rules of IHL. In Resolution SAI-SUBB-AOI-D-030-2019 of October 9, 2019, it analyzed whether in a conduct previously classified in ordinary justice as terrorism, IHL had been violated, and after determining that the principle of distinction was violated, proceeding to deny the benefit of amnesty23.

In the case, the SAI considered that the Superior School of War and the members of the Public Force who were injured by the car bomb are not victims based on the assessment carried out by IHL, but it maintained them as intervenors in the procedure. Meanwhile, it maintained the recognition of the quality of victims of the Military University of Nueva Granada and the civilians affected by the detonation of the car bomb. The decision to consider only the civilian population and the University victims is based on the fact that the conduct of the appearing party did not constitute a violation of IHL. Although in the SJP the persons recognized as victims in the ordinary justice or the Unique Registry of Victims, among other sources of accreditation, retain said quality during the procedure until the SJP re-qualifies the behaviors by which they were affected, once this is done, the recognition of the quality of victim can also vary24. In the case, the recognition of the quality of victims varied from the reclassification of the conduct carried out by the SAI from IHL.

However, it is considered that the point on the recognition of the victims merited a broader basis to support the definition adopted of victim, which included a reference to its development in the international and national legal framework on the matter. For example, subsection 1 of art. 3 of Law 1448 of 2011 establishes a concept of victim that includes members of the Public Force who “have suffered damage due to events that occurred after the 1st. January 1985, as a consequence of violations of International Humanitarian Law or of serious and manifest violations of international Human Rights standards, which occurred during the internal armed conflict ”. Thus, IHL is not the only criterion to establish who can be considered victims for the purposes of said Law. Another example is subsection 4 of art. 5 of the Justice and Peace Law, which considered members of the Public Force who had “suffered temporary or permanent injuries that cause some type of physical, mental and / or sensory disability (visual or hearing), or impairment of their fundamental rights, as a consequence of the actions of any member of the armed groups organized outside the law ”, without demanding that the damage be the result of a violation of IHL25. Although these definitions are applicable within the framework of other laws than those implemented by the SJP, the use of broader notions of victim in other regulations made it important to develop a deeper analysis to determine and support the concept of victim applicable by the SAI.

Likewise, it would have been appropriate for the SAI to explain to the military affected by the car bomb what effects the determination not to recognize them as victims in the decision had for them, when before the process they had been recognized as such, and what guarantees they could have regarding the contributions to the truth and the public recognition hearings that the appearing party should carry out within the framework of the conditionality regime. In any case, the soldiers affected by the car bomb had the right to file appeals against the Resolution26 and, in effect, they did27. Additionally, it must be taken into account that this decision does not deny the possibility that members of the Public Force may be recognized as victims in different specific circumstances, such as, for example, when they suffer damages caused by violations of IHL, or that they are according to their special regime.

1 The rebellion is typified in art. 467 of the Penal Code: “Those who, through the use of arms, intend to overthrow the National Government, or suppress or modify the constitutional or legal regime in force, will incur in prison for ninety-six (96) to one hundred sixty-two (162) months and a fine of one hundred thirty-three point thirty-three (133.33) to three hundred (300) current legal monthly minimum wages”.

2 The sedition is typified inart. 468 of the Penal Code: “Those who, through the use of weapons, intend to temporarily prevent the free operation of the constitutional or legal regime in force, shall incur in prison from thirty-two (32) to one hundred forty-four (144) months and a fine of sixty and six point sixty-six (66.66) to one hundred fifty (150) current legal monthly minimum wages”.

3 The coup is typified in art. 469 of the Penal Code: "Those who in a tumultuous manner violently demand from the authority the execution or omission of any act proper to their functions, shall incur in prison from sixteen (16) to thirty-six (36) months”.

4 The conspiracy is typified in art. 471 of the Penal Code: "Those who agree to commit the crime of rebellion or sedition, will incur, for this conduct alone, in prison for sixteen (16) to thirty-six (36) months”.

5 The seduction, usurpation and illegal retention of command is typified in art. 472 of the Penal Code: “Anyone who, for the purpose of committing the crime of rebellion or sedition, seduces armed forces personnel, usurps military or police command, or illegally retains political, military or police command, shall incur in prison of sixteen ( 16) to thirty-six (36) months”.

6 Law 1820 of 2016, art. 41.

7 Council of State. Second Section, Subsection A. Judgment of January 22, 2019. File. 25000-23-42-000-2019-00018-01. Counselor: William Hernández Gómez.

8 SJP Review Section. Sentence SRT-ST-096/2019 of March 20, 2019.

9 SJP (February 28, 2020). The SJP in figures. Available at: https://www.jep.gov.co/Infografas/cifras-febrero-28.pdf

10 Amnesty and Pardon Panel. Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020 of February 12, 2020, para. 102.

11 See: Rome Statute. Art. 8.

12 In accordance with Rule 12 of customary IHL: “Indiscriminate attacks are those: (a) which are not directed at a specific military objective; (b) which employ a method or means of combat which cannot be directed at a specific military objective; or (c) which employ a method or means of combat the effects of which cannot be limited as required by international humanitarian law; and consequently, in each such case, are of a nature to strike military objectives and civilians or civilian objects without distinction”. Indiscriminate attacks are prohibited, in accordance with Rule 11 of customary IHL. See also the art. 3.3. of Protocol II on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps, and other Devices. According to the SAI analysis in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, the car bomb was (and could be) directed against a specific and specific military objective (the Superior School of War), and its effects could be controlled by the FARC-EP, since its objective could be limited, as long as it had a timer for its activation, and the scope of its damage, since its impact range depended on the explosive charge. Likewise, in the specific case, no indiscriminate effects were observed on property or civilians.

13 In accordance with art. 2.2 of Protocol II on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps, and other Devices: “"Booby-trap" means any device or material which is designed, constructed or adapted to kill or injure and which functions unexpectedly when a person disturbs or approaches an apparently harmless object or performs an apparently safe act”. On the restrictions for its use, see arts. 2.4 and 6. The SAI, in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, considered that the car bomb was not a booby trap because it had a detonation mechanism whose activation was not the result of the approach of the victims or that some of them move it.

The art. 3.3.c. of Protocol II on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps, and other Devices and the Rule 70 of customary IHL establish, respectively, that weapons that cause unnecessary or manifestly excessive suffering in relation to the military advantage obtained may not be used. This did not occur in the case of the car bomb at the Superior School of War in 2006, according to the SAI analysis in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020.

According to the art. 3.3. of Protocol II on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps, and other Devices, weapons cannot be used as a means of attacking the population or civilian objects. In Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, the SAI determined that the car bomb was used against a military target.

According to art. 6.1.a. of Protocol II on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps, and other Devices, portable devices built to contain explosive material and detonate when touched are prohibited. The SAI, in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, established that the car bomb did not fit into this category, since it was a vehicle, that is, a means of transport.

In accordance with art. 3.4. of Protocol II on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps, and other Devices, “All feasible precautions shall be taken to protect civilians from the effects of weapons to which this Article applies. Feasible precautions are those precautions which are practicable or practically possible taking into account all circumstances ruling at the time, including humanitarian and military considerations”. According to the SAI analysis in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, the car bomb was detonated in an area of concentration of civilians, but close to the military objective against which the attack was directed and taking viable precautionary measures to protect civilians.

14 The Customary Norm 7 of NHL establishes that: “The parties to the conflict must at all times distinguish between civilian objects and military objectives. Attacks may only be directed against military objectives. Attacks must not be directed against civilian objects”.

15 In accordance with the art. 2.4. of Protocol II on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps, and other Devices: "Military objective" means, so far as objects are concerned, any object which by its nature, location, purpose or use makes an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage”. In Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, the SAI determined that the Superior School of War was a military objective in the context of the internal armed conflict, because it was an asset that contributed effectively to the military action of the Force. Public: its objective was to train senior commanders in charge of planning and conducting operations, and both its nature and its directive composition were military in nature. Furthermore, it was a military objective because its destruction offered a definite military advantage, especially in the context of a government policy of security, defense, intelligence and counterintelligence. On the one hand, with its destruction, the FARC-EP could demonstrate a severe blow to one of the institutions that are responsible for maintaining the legal and constitutional regime, through the infiltration of a very important institution of military training in the country. On the other hand, this could also allow them to discharge military officers.

16 On the precautionary principle, see: Customary Norms 15-24 of IHL.

17 According to the SAI analysis in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, the infiltration of the appearing party was an act of planning the event. Within the framework of this, the appearing party provided information and sketches to an intelligence and communications front of the FARC-EP, which carried out their verification. The information and the sketches were about the plans of the School, the location of the classrooms where they studied the military, the parking lot used by the military and the location of the Military University. Additionally, the car bomb was located in front of the school's classroom building, and its explosion reached, mainly, said building and, to a lesser extent, a part of the University. In addition, the detonation occurred at 8:30 a.m., at which time a class was taught for a large group of members of the Public Force.

18 According to the Customary Norm 14 of IHL: “Launching an attack which may be expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof, which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated, is prohibited”.

19 According to the analysis of the SAI in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, the military advantage was foreseen at the time of planning the attack, since it was aimed at the people who attended the General Staff course. In addition, the Minister of Defense was present. Likewise, it was expected to account for the vulnerability of the Public Force and affect its institutional stability.

20 According to the SAI analysis in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, the military advantage was concrete, because it put at risk 218 military personnel who were taking a course at that time and called into question the work of intelligence and counterintelligence of the State.

21 According to SAI's analysis in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, the military advantage was direct, because it had the ability to produce the desired effects by itself.

22 According to the SAI analysis in Resolution SAI-AOI-D-003-2020, the damage to civilians was not disproportionate to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated, since there were no deaths or serious injuries and the damage to the University were also minor.

23 See: Resolutions SAI-AOI-SUBA-D-022-2019 of May 13, 2019, SAI-AOI-SUBA-D-011-2019 of April 30, 2019 and SAI-AOI-009-2019 of February 4 of 2019.

24 Appeal Section. Order TP-SA 193 of 2019 of June 5, 2019, para. 18.

25 In the analysis of the constitutionality of this provision, by means of Sentence C-575 of 2006 (M.P. Álvaro Tafur Galvis), the Constitutional Court indicated that international humanitarian law does not prohibit the State from “granting or attributing the status of victim to members of the public force in the circumstances referred to in the referred law”.

26 Law 1922 of 2018, arts. 46, 12 y 13.

27Blu Radio (March 3, 2020). Military victims of high school bombing appeal JEP decision on ‘Mata Hari’. Available at: https://www.bluradio.com/judicial/militares-victimas-de-bomba-en-escuela-superior-apelan-decision-de-jep-sobre-mata-hari-243613-ie430